The Best Post-George Floyd Reform Was Dodging the Worst Ones

How the Non-Revolution Helped Stop the Bloodshed

The fifth anniversary of George Floyd’s murder passed, mostly, without drama. No mass vigils, no police chiefs marching in kente cloth. A few muted segments on the evening news. Maybe a tweet. If the summer of 2020 was a reckoning, this spring was a shoulder shrug.

Still, something curious is happening—not on the streets, but in the minds of citizens. Gallup reports that Black Americans’ confidence in their local police forces has risen for three consecutive years. It now sits at 64 percent, up six points from last year and higher than it was the year Floyd died. That’s still below the 77 percent confidence level among white Americans, but the gap has narrowed considerably. Nearly two-thirds of Black Americans now say they are satisfied with the police in their community.

This is not the story we were told to expect. Since 2020, the narrative has held that policing is irreparably broken, particularly for people of color. Activists demanded sweeping reforms. Politicians promised them. Editorial boards solemnly endorsed them. And yet, despite very few of those reforms being enacted—Congress passed no legislation; four states tinkered with qualified immunity; chokeholds were banned in some jurisdictions and quietly used anyway—public trust has rebounded. Especially among those who were said to have lost it.

There are several ways to explain this, but the simplest is that reality reasserted itself—and that reality in America is violent and too often deadly, nowhere near the dystopic situation described in the most viral accounts. For a time, Americans were saturated with images of police abuse. Every shooting, every shove, every foot on a neck went viral. On the very day of the Derek Chauvin verdict, an Ohio teenager, shot by police as her knife was about to plunge into the chest of another teenaged girl, became a cause célèbre. An armed man in Wisconsin attempting to speed off with children in the back seat of a car that wasn’t his became near-martyr and political symbol. The media served these stories hot.

They came in as alerts on our phones, framed as proof that nothing had changed, that justice remained elusive. The public—already disoriented by a pandemic, political chaos, and what seemed like the collapse of every system—were powerless in the face of what they were told was a moral emergency demanding immediate action against unchecked police violence.

The effect was measurable. When asked how many unarmed Black men police kill each year, liberal respondents most frequently guessed 100, the most liberal guessed 1000. The actual number, depending on the definition of “unarmed,” was in the teens or lower. If this was a national conversation, it had drifted far from its empirical moorings.

That’s not to say police misconduct is unimportant. But it is to say we’ve seen this pattern before. In the 1980s, “stranger danger” convinced American parents that their children were at constant risk of abduction, even as rates were low and falling. In hindsight, many recognized the panic for what it was. But in 2020, those same good-hearted citizens—ashamed that people in their milieu once fell for media distortions exaggerating the threat of Black assailants—failed to apply the same scrutiny. Now, it was police officers who became the objects of fear, and the message was stark: if you were Black and interacting with law enforcement, you were in danger.

And yet, over the decade in which comprehensive data on police killings has been tracked, the numbers have been remarkably stable. Around 1,000 people killed annually. The Washington Post database counts 4,666 white victims and 2,492 Black ones. The public, meanwhile, imagined a very different distribution: more Black than white victims, more unarmed than not. The facts didn’t penetrate. The narrative did.

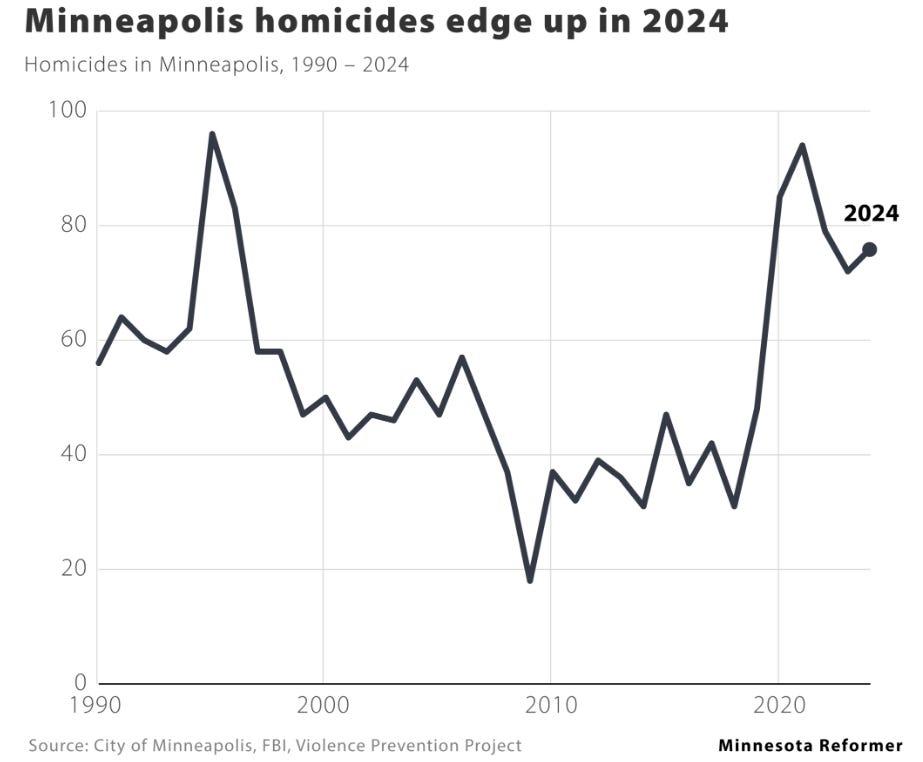

Narratives have consequences and stories have morals. In the aftermath of Floyd’s murder, cities across the country pledged to “defund the police.” Some actually did. A 2021 Brennan Center report cheered on the "victories" of defunding they could document, specifically Los Angeles and Austin, Texas. It's true that Austin cut its police budget from $434 million to $292 million in 2021. The Guardian as recently as this year, cited this budget cut as "progress." They did not track the changes in homicides in the city, which more than doubled, from 33 in 2019, to 43 in 2020 to 88 when the funding cuts were implemented in 2021. The budget was quickly restored. In Minneapolis, the police force shrank from nearly 900 officers to just 570—not by policy but by attrition. The city’s murder rate spiked, with homicides jumping from 46 in 2019 to 97 in 2021 and remaining more than triple the national rate through 2024.

Portland, Oregon, went further and fared worse: its homicides rose from 36 in 2019 to 92 in 2021, the highest in city history. The two large police departments with the lowest officer-to-resident ratio were, not coincidently, Minneapolis and Portland.

Faced with horrific imagery and actual documented cases of abuse, it's no surprise that the public reacted strongly. The outpouring of reform sentiment was expected and, if anything, reflected a shared sense of empathy and humanity. But that didn’t make the protest demands grounded, or the slogan-driven solutions of public officials any more substantive. The public showed itself to be idealistic in its hopes for policing, but realistic when it came to judging the results of some of the more muddled, impractical reforms. In Los Angeles, District Attorney George Gascón—elected amid calls for reform—presided over a surge in murders: 355 in 2020, up from under 300 the year before. In his first full year in office, the number hit 402. It has not fallen below 300 since. Critics blamed him. Supporters called the criticism fearmongering. Fast forward to this past weekend, when USC law professor Jody Armour appeared in one of KTLA’s 'Police Reform Five Years Later' segments, describing Gascón as embodying the “politics of solidarity and compassion”—a politics, he argued, that has since been overtaken by “a politics of fear.” What? That's a backward reading of a public reaction to a district attorney who presided over an unprecedented rise in murder. Luckily, the leaders of the reform community are subject to the veto of the actual community.

The thing about policing in America is that, for all the talk of abolition and transformation, most people—especially Black people—don’t actually want it gone. They want it to work. Polls show this consistently. Support dips in times of scandal, then rebounds.

To most Americans, the crime spike that resulted from the poor policy choices made in the wake of George Floyd was more pressing than police reform itself. In hindsight, focusing on the 250 or so annual police killings of Black men—serious as that number is—is far less urgent when compared to the more than 11,000 Black men murdered each year by others. Focusing on the threat posed by police wasn’t trivial, but compared to the broader pattern of slaughter in America, it was an indulgence the public quickly abandoned once that usual pattern reasserted itself with even deadlier force.

And while that is bleak, the emerging picture is brighter. Reason Magazine recently speculated that 2025 could end with the lowest murder rate ever recorded. If that happens, it will occur not because the George Floyd protest demands were met, but because—by and large—they weren’t.

That’s a reminder that the most important reforms are sometimes the ones we don’t tweet about, or post black squares in support of. Sometimes, they’re the ones that quietly ensure more cops show up when you call—and fewer people die when they do.

Mom of Seattle police officer here. On Saturday, and to a lesser degree yesterday, "protesters" attacked a police line, separating them from a rally by a Christian (and anti-gay) church gathering. Eight hours of praise songs, apparently. One officer went to the hospital with a head injury. Rather than framing these incidents as an attack on free speech and law enforcement, the mayor decried the Christian right-wing message. Hopefully, there isn't traction for another summer of this stuff. Interestingly, and depressingly, the chant of the protesters was "IDF, KKK, SPD, all the same" and many wore keffiyeh's.

This doesn't contradict the major premise of your article, which seems accurate to me.